- Home

- News

- Opinion

- Entertainment

- Classified

- About Us

MLK Breakfast

MLK Breakfast- Community

- Foundation

- Obituaries

- Donate

11-07-2024 6:08 pm • PDX and SEA Weather

Her parents and grandparents had all died young, a fact Cosgrove carried with her as she sold her business at the age of 50 to take up painting full-time. Now 72, she says, “I’m here! And I’m doing great. And so I had to kind of shift and say, ‘Oh, if I’m not going to die (early), what the heck am I going to do with the rest of my life?’ And rethink that.”

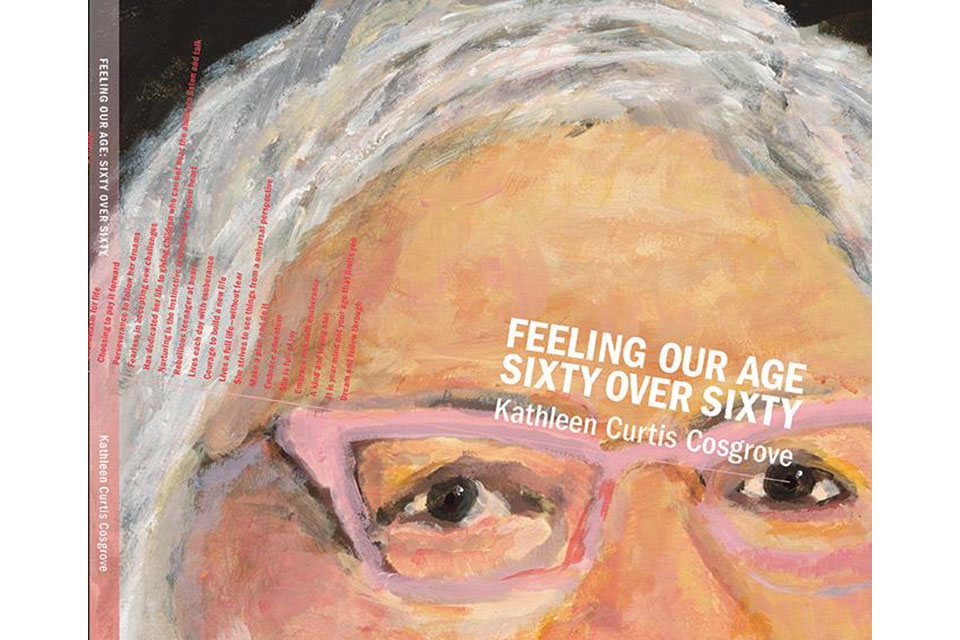

Her curiosity about aging and her frustrations during the pandemic inspired her to speak with other women of her generational cohort. The result is ‘Feeling Our Age - Sixty over Sixty,’ a book of 64 portraits of women Cosgrove painted, accompanied by their own words on advancing in years.

“I really started out thinking that what this project was about was age discrimination and changing outdated attitudes and stereotypes,” Cosgrove told The Skanner. “I was very startled when I started talking to people and asking them how they felt during this age, and the information I was getting back was very uplifting – the stories about the things they intend to do from this point forward, how great this time in their life was.”

Artist Kathleen Cosgrove

Artist Kathleen Cosgrove

Cosgrove’s subjects include former legislators, tribal elders, a nurse from Kenya and The Skanner News Group’s cofounder and Executive Editor, Bobbie Dore Foster. The youngest is a Native woman of 52, describing her ambitions of being an elder in her community.

The 'Feeling Our Age' art exhibit grand opening and book-signing will be Thursday, June 20 from 4 to 7 p.m. at the Watermark in the Pearl, 1540 NW 13th Ave.

“It was just amazing,” Cosgrove said. “Because here I was being this grumpy person, mad that people were telling me I was old and vulnerable, and I started listening to these stories and it really changed the way I feel. I realize that’s what the book needed to be about: how vital people of this age are, and how they are such untapped resources and they have so much to give.”

Margaret Carter

Margaret Carter Ruby Haughton-Pitts“I actually have really strong feelings about aging,” ‘Sixty Over Sixty’ participant Ruby Haughton-Pitts, who once led the Oregon AARP, told The Skanner. “Unfortunately we live in a society that doesn’t value aging as much as it once did, and I really think that it’s extremely important to one, value your past, and two, encourage the future. And they’re linked together, and I think in the rush of the world, people can forget that. And so I really felt like Kathleen’s heart for this project really brought that forward for me in a very special way.”

Ruby Haughton-Pitts“I actually have really strong feelings about aging,” ‘Sixty Over Sixty’ participant Ruby Haughton-Pitts, who once led the Oregon AARP, told The Skanner. “Unfortunately we live in a society that doesn’t value aging as much as it once did, and I really think that it’s extremely important to one, value your past, and two, encourage the future. And they’re linked together, and I think in the rush of the world, people can forget that. And so I really felt like Kathleen’s heart for this project really brought that forward for me in a very special way.”

“I have an interesting view about the ‘aged’ process,” fellow participant Margaret Carter told The Skanner. “My view is that I might be 88 in years, but my body and my mind says something else so I act out how I view myself as an aged woman in society.

"You notice I have never used the word ‘old,’ I use the word ‘aged.’”

Carter became the first Black woman elected to the Oregon legislature, where she served as a representative for 14 years before becoming a senator. Her political life started after she had escaped an abusive marriage, raised five children, returned to school for a masters in counseling and served as faculty of Portland Community College for nearly 30 years.

Not surprisingly, Carter rejects the idea that age should dictate occupation or where one is in life.

“I think that it’s important for people to determine who they want to be by the time they’re a certain age,” Carter said, “and what they’re going to do to magnify that in a world that puts limitations on people.”

In fact, Carter knew Cosgrove from their time in the state capital.

“When I was in the legislature she was a lobbyist, and it was women just making their way in that field because most of the lobbyists over the years have been men,” Carter said. “Kathleen was soft but firm, well researched, and she has a view beyond what the average woman would think about women and how we are viewed in society.”

That experience highlights the monumental shifts in women’s legal rights and social standing Carter, Cosgrove and others over 60 have lived through.

“I remember in my early years working for a congressman and there were certain positions I couldn’t have because I wasn’t allowed to staff him during travel time – because people would talk,” Cosgrove said. “So any kind of one-on-one staffing that involved any kind of travel, they would always send a male. And so it was very hard to get the same level of experience because I had barriers to my doing the same things that my male counterpart would do.”

She ultimately founded her own lobbying firm, with a focus on advocating for the arts. After turning 50, Cosgrove attended the Pacific Northwest College of Art and gravitated toward a more abstract style of expression. For ‘Sixty Over Sixty,’ she had to teach herself how to paint portraits.

“What I realized is I wanted to use bright colors instead of white mattes.

"I just felt like I wanted the portraits to sort of say, ‘Look at me, I’m here.’”

Cosgrove found her subjects in her own circle and also through outreach online. For each subject, she worked through a series of photos to create a composite of the woman.

“I really liked photos that had their hands touching their faces in the portrait, because I think that’s something we do: We look at ourselves as we get older and think, ‘Oh, it can’t be – this must be my mother in the mirror!’”Carter agreed.

“It’s not meant to show a distorted view of women – it’s meant to show that as we grow older, we don’t look the same as we did when we were younger,” she said. “And I think that that creates a kind of attitude of vulnerability, but positive. And I think that’s a positive way for older women to be seen without feeling as if something is ugly or that something distorts the view of who they really are.”

Although there is a large body of research to suggest that most of us grow happier as we age, the risk of social isolation also increases.

Haughton-Pitts argued that technology has largely displaced generational wisdom.

“I think that because we have so many tools to ‘look it up’ that Google has become the authority, as opposed to those that came before us who lived it,” she said. “And sitting down and having the conversations with people will actually give you far more insight than Google ever will.”

For Cosgrove, that disconnect has shown in other areas of daily life.

“I really noticed myself having a hard time with some transitions and feeling like the older I became, the more invisible I got,” Cosgrove said. “Little things – clerks would not notice you were there, or you’re always served last at the restaurant. Silly little things, but they all seemed to add up. Then the pandemic hit, and it just exaggerated everything.”

Cosgrove resented feeling further isolated – and she found herself haunted by a family tragedy.

“I was told that my grandmother, my mother's mother, had died in childbirth when her brother was born, about a year after she was,” Cosgrove said. “I found out when I was 16 that in fact she had not died. It was during the Spanish flu and she got the flu from the doctor, and there was a high fever and brain damage and she was put in an asylum, basically. And I never met her, and she was alive. She was locked away all that time. Then here we are hit by the pandemic and it feels like that’s what they’re doing to older persons all over again. They weren’t – that was just my take on it because of what I’d gone through.”

Working on ‘Sixty Over Sixty’ served as a kind of catharsis for Cosgrove. As Carter puts it: “I’m not going to let anybody put me in the casket before the time comes. There is still vibrancy in all of us who have the energy.”

For more info on the project, visit https://kccosgrove.com.